Seal of the month - 2013-2019

2018 - 2017 - 2016 - 2015 - 2014 - 2013

2019

Summer 2019

Εις τον αφρόν, εις τον αφρόν της θάλασσας...

Happy summer!

June 2019

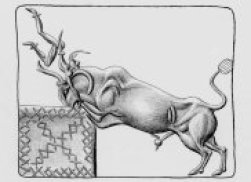

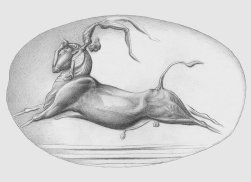

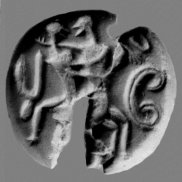

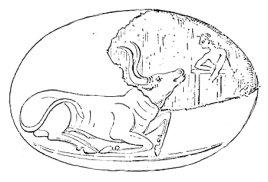

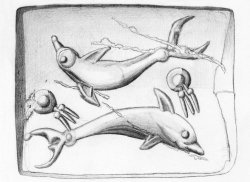

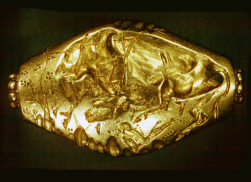

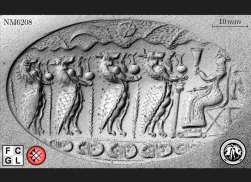

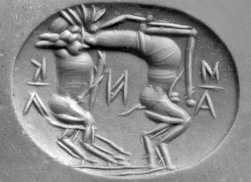

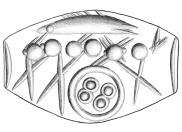

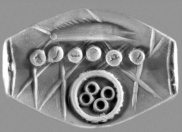

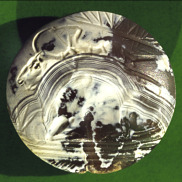

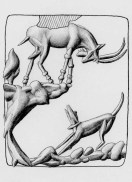

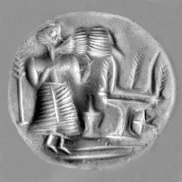

CMS VI no. 181; II,6 nos. 44, 43

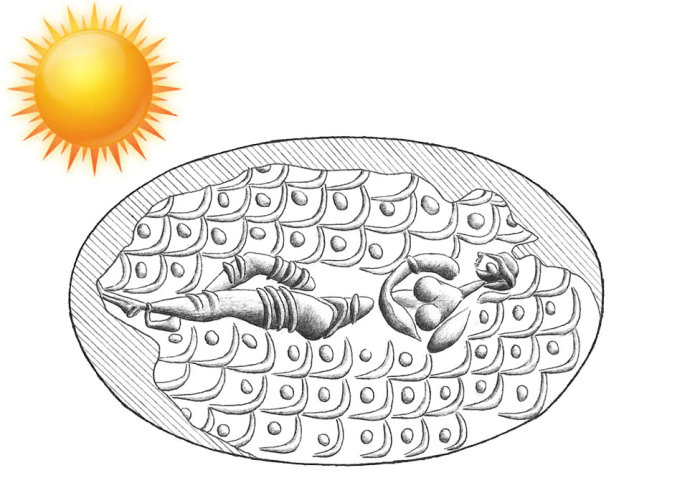

A cushion and the impressions of two golden signet rings on several nodules

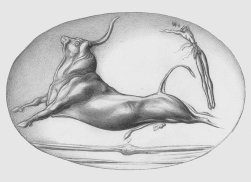

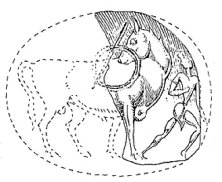

Three seal faces showing different phases of bull-leaping: 1. The animal climbs with its front legs on a quadrangular feature and the bull leaper reaches for its neck in the process of jumping over it. 2. The bull is running (flying gallop) as the leaper grasps its neck and executes a back flip over it. 3. The bull-leaper is in the air behind the running animal with feet directed towards the ground and thus shown in the moment he has completed the jump over the bull and is landing on the ground behind it. In this last image, the bull leaper is shown in frontal view.

CMS VI no. 181: Priene?; Stylistic Dating: MM III/LM I

CMS II,6 no. 44: Agia Triada; but the same impression also from Gournia, Sklavokambos. Stylistic Dating: LM I. Context: LM IB

CMS II,6 no. 43: Agia Triada; but the same impression also from Gournia, Sklavokambos, Kato Zakros; Stylistic Dating: LM I. Context: LM IB

Commentary

The strength of the animal is expressed by its voluminous muscular body and the athletic feat of the bull-leaper with his, by contrast, ‘elastic’ sinuous frame. Bull-leapers on neopalatial seal faces are fine and agile figures while after LM II, bull-leapers become larger and heavier, in some cases shown even larger than the bull.

Evans was the first to try to reconstruct the phases of the Minoan sport. Following Evans and then Sakellariou’s work, John Younger suggested that Aegean bull-leaping images depict three different ways of executing the sport. In Evans’s Schema (mainly neopalatial, see also here) the leaper grabs the animal by the horns, does a back flip over its back, steps on its rump and jumps over it again towards the ground. In the Schema of the Diving Leaper (LB I-III) the bull leaper dives towards the shoulders of the bull from a higher point, and then carries out a handspring and back flip to land on the ground behind the bull. In The Schema of the Floating Leaper (LB III) the leaper is always shown above the bull with his front side facing the animal’s back and his legs bent. This latter schema is mainly found on seals of the last phases of the Late Bronze Age and is more favoured in the mainland than on Crete. Given the late dating of this schema, the stronger connection with the mainland and the fact that the leaper is always shown ‘frozen’ in the same position, Younger has suggested that this latter scheme could be a decorative one developed from images of bull-leaping when the sport was not executed anymore (and/or at places where it was never executed). Younger has also suggested that among the three schemas the only one that seems to realistically depict the sport is the second, the Schema of the Diving Leaper.

According to Younger, the first image presented here belongs to his second scheme, the second to his first and the third to both (Younger’s ‘alighting leapers’). However, as the images are placed here, they appear to belong to the same general type of execution of the sport, especially as the leaper in both the first and the second image grasps the animal’s neck (and not horns: Evan’s Schema). It is therefore possible that they both belong to the Schema of the Diving Leaper and represent scenes from the actual sport.

Maria Anastasiadou

References:

A. Evans. 1930. The Palace of Minos, III. London (MacMillan).

J. Mcinerney. 2011. Bulls and Bull-Leaping in the Minoan World. Expedition 53.3: 6-13.

A. Sakellariou. 1958. Les cachets minoens de la collection Giamalakis. EtCret 10. Paris (Geuthner).

J. G. Younger. 1976. Bronze Age Representations of Aegean Bull-Leaping. AJA 80.2: 125–37.

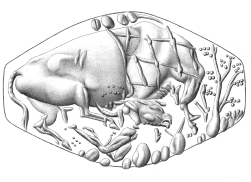

March/April 2019 (by Fritz Blakolmer)

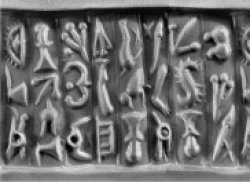

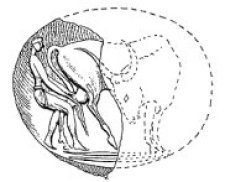

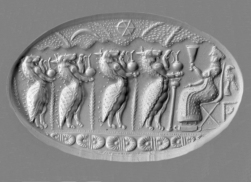

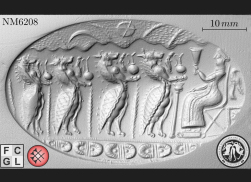

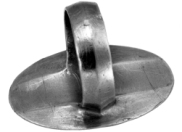

CMS I no. 379

Impressions of a metal ring on three clay nodules

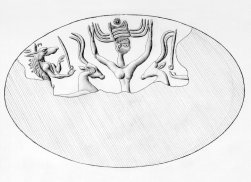

A symmetrical composition consisting of a central divine figure of female sex, as indicated by the breasts, which is flanked on each side by a scene that combines two creatures: a bull that is accompanied by a Minoan genius with a distinct type of knife.

From Pylos, Palace, Southwest Building

Context: LH IIIB2 destruction horizon

Stylistic dating: LB II late/LB IIIA1

The nodules are kept at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens

Commentary

Although this image of a metal ring is attested by three fragmented seal impressions, only its upper part is preserved and thus permits us to discuss merely half a ‘seal image of the month’. From a typological point of view, it presents the emblematic, symbolic motif of a Potnia Theron which is popular mainly in post-Neopalatial glyptic. Its distinct iconography, though, is unique and worth a closer analysis.

The goddess in the centre with naked torso, raised arms and, as it seems, short hair wears a variant of the so-called ‘snake frame’ upon her head. This figure clearly belongs to the Minoan type of the ‘Goddess with Snake Frame’ that is well-known especially in the glyptic of post-Neopalatial Crete. In this seal image, though, the special head-dress exhibits some familiarity with a polos decorated with multiple horns sticking out on both sides inspired from Near Eastern or Hittite images. Furthermore, this Minoan headgear is crowned by a symbolic double-axe and a rosette.

The Minoan figure of the ‘Goddess with Snake Frame’ normally appears as flanked by griffins or lions and can probably be associated with the throne-room of the palace at Knossos with its mural painting of antithetical recumbent griffins guarding the throne and the figure seated on it respectively. In contrast to that, the goddess in the seal image from Pylos is flanked on both sides by completely different figures: instead of ‘creatures of power’ that are subdued by the goddess, an entire scene is represented that can be reconstructed as the motif of a bull and a Minoan genius crossing each other; most probably the demon stands behind the bull. Although Minoan genii were occasionally depicted as flanking and protecting divine figures, in the present image they rather seem to guide the bulls – a common Minoan seal motif. In the iconography of the entire Aegean Bronze Age bulls almost never appear as attendants of or dominated by male or female deities making an interpretation of the bulls as protecting animals of the ‘Goddess with Snake Frame’ in the Pylos seal image highly improbable.

The key for our understanding of this unique image could be the knife which is not really held by the Minoan genii but simply added to their hand-like paws, probably in order to present this type of knife in its entirety. Although the knife with a terminal ring is well known from a series of archaeological contexts, the definition of its exact function causes some problem to us. Nonetheless, its probable occurrence in ritual scenes such as the procession fresco in the staircase of Xeste 4 at Akrotiri in Thera suggests that this type of knife should not exclusively be seen as a battle-knife but was associated with offering or that ritual slaying was at least one of the purposes of this instrument. Thus, if my interpretation is correct, the lateral motifs of this seal image can be read by us as a Minoan genius with a slaughtering knife in his hand and accompanying a bull. As a consequence, the common emblem of a Potnia Theron was combined with the pictorial allusion to a ritual scene that can hardly be interpreted other than the slaughtering and offering of a bull. In Aegean imagery the figure of the Minoan genius is often depicted in motifs that can be associated with sacerdotal functions such as transporting quadrupeds (to be offered) or holding their characteristic libation jug. It forms a striking peculiarity of Aegean iconography that no human figure was depicted in conducting or alluding to sacrificial rituals in front of a deity. In order to circumvent this obvious taboo, the Minoan genius replaced human worshippers or priests.

As a consequence, the divine image of this LB II-IIIA metal ring exemplifies well a certain distance from the standardized Minoan iconography. The original form of the orientalising ‘snake frame’ seems to have been replaced by a slightly different head-gear inspired by the Near East. Instead of the conventional creatures of power, the goddess is flanked by an unusual motif alluding to bull sacrifice conducted by a hybrid being of semi-divine character, the Minoan genius. This highly complex seal image, therefore, is full of symbolism and exhibits a new iconographical creativity by combining traditional Minoan elements with old and possibly also new inspirations from the Near East, perhaps in a kind of ‘interpretatio mycenaea’, and by presenting the deity in closer relation with the sacrificial ritual in its honour.

Fritz Blakolmer, Vienna, March 2019

References

I. Pini, Die Tonplomben aus dem Nestorpalast von Pylos (Mayence 1997) 7-8, cat. no. 12, pl. 4.

F. Blakolmer, Mycenaean iconography: dependency, hybridity and creativity, in: P. P. Iossif - W. van de Put (eds.), Greek Iconographies: Identities and Media in Context. A Seminar organized by the Netherlands Institute at Athens and the Belgian School at Athens, Pharos 22(1) (Athens 2016) 27-47, esp. 33-35.

F. Blakolmer, Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo? Character, symbolism and hierarchy of animals and supernatural creatures in Minoan and Mycenaean iconography, Creta Antica 17, 2016 (2018), 97-183.

February 2019 ('Dinner for two: Minoan Valentine')

Impression of a soft stone lentoid on a string nodule

Two humans in profile are standing on either side of a tripodic vessel (tripod cooking pot?) and hold an oblong object in its interior. Above the pot, there is a plant element.

Stylistic dating: Late Bronze Age

Commentary

The right figure is wearing a long garment that could represent a dress or skirt but probably not a robe since it does not appear to be fastened in the front. Because of this the CMS has identified the figure as female despite the fact that it has neither long hair (loose or tied in a bun) nor female breasts, elements that are commonly used to render female figures.

The two figures are engaged in an action of either stirring something with the help of a rod-shaped element or grinding/crushing with the help of a pestle. While it is not possible to say with certainty what action is depicted, the shape of the vessel which is known to have been used in cooking could suggest that the figures are involved in the act of food preparation. The image on this seal could, therefore, be seen like a snapshot of everyday life in the Bronze Age Aegean.

Such images are rather rare on Aegean glyptic and, when they appear, they provide an exceptional insight into the way of life in these societies. Seal iconography is an invaluable source in our attempt to visualise prehistoric life in the Aegean, especially since no deciphered texts apart from Linear B exist that provide information about everyday life during the Bronze Age. These images can be likened to ‘photographs’ from the past that attest nicely to similarities between life then and now:

Fishing - Sailing - Hunting - Dog welcoming owner - Playing ‘backgammon’ - Milking

Maria Anastasiadou

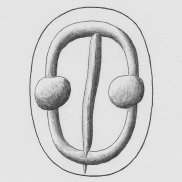

January 2019 (by Diana Wolf)

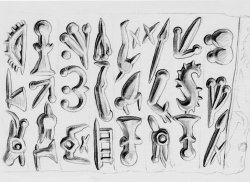

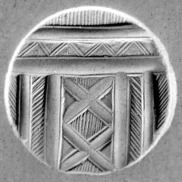

CMS XI 244

Cushion seal, bronze (?)

Without provenance

Stylistic dating: LM I–II

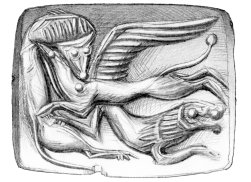

A pair of lions and a griffin are engraved in dynamic poses on this seal face. While one lion is depicted bounding from left to right (impression) in the lower part, the griffin is leaping in the opposite direction in the middle of the scene. The second lion is displayed along the left vertical axis and is shown pouncing on the griffin, biting it in the neck. Its body seems to wrap around the griffin and the hindlegs of the first lion, probably a result of the limited amount of space on the rectangular seal face and the attempt to create perspective.

Commentary

Griffins are fantastic creatures of a Near Eastern origin and attested on Crete from MM II/III onwards. The hybrid originated in the early Elamite period, after which its iconography spread to predynastic Egypt. At the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE, the Egyptian griffin came to Syria before moving on to the Aegean world (Morgan 1988, 49–50; Aruz 2008, 288–90). At each of these stages, its iconography underwent changes. While Classical Antiquity produced griffins of various types, such as lion-, serpent-, or ravener-headed creatures with the winged body of a lion, the Aegean griffin always had the head and wings of a bird of prey and the body of a lion (Delplace 1967, 77–78). These features were taken over from Late Old Syrian and Classical Syrian style (Aruz 2008, 108). All the while, Aegean artisans regularly varied iconographical details and themes and even configured female griffins, which are otherwise unattested in the neighboring cultures.

The griffin proved a popular motif from its earliest time in Crete, a fact proven by early seal impressions from Protopalatial sites such as Malia and Phaistos. Interestingly, it is prominent on further iconographic media such as wall-paintings, painted vessels, and larnakes (for more, see Morgan 1988, 49–54). With 21 known examples of metal seals, mostly in gold, but also in bronze, it is the most prominent fantastic creature featured in this high-value material. There are a variety of griffin depictions, from static single creatures to narrative scenes of hunting and drawing chariots, and finally heraldic compositions and animal-mastery scenes (Blakolmer 2016, 64). Especially in wall-paintings they typically accompany figures of power such as a seated goddess or a real human that would be sitting on a high-backed throne as in Knossos.

Lions, unlike griffins, are animals that occur in the natural world. They did not appear on Crete and were probably chiefly known by their iconography, which was likewise imported from the east. Although some bones have been found on the mainland, the question of the animal’s occurrence remains a matter of scholarly debate. Just like griffins, lions exerted a strong fascination on people in the Bronze Age. They are not only a highly recurrent motif on seals, but, like griffins, they are present on various other media such as dagger pommels and inlaid blades, wall-paintings, vessels and sculpture – most prominently the lion gate of Mycenae (Shapland 2010). Often, they are depicted as predators of fallow, wild goats and even bulls. In other scenes, they are encountered by human warrior-hunters and prove a dangerous prey for them. Thus, lions always afford danger to animals as well as humans. The seal discussed here perpetuates this danger on another level: a metaphysical sphere of fantastic creatures, represented by the griffin.

The relationship of griffins and lions is not immediately clear; while both attack animals of prey, occasionally even together, other scenes show griffins attacking lions or lions attacking griffins. Whereas lions are frequently hunted by humans, there is only one possible case of griffins hunted by men. The creatures’ roles in regard to humans differ from their mutual relation to each another. Moreover, both lions and griffins can appear in heraldic animal mastery scenes, again either with their specimens or, combining one lion and one griffin. To sum up, there is no static hierarchy between both creatures as either can be harmed by the other. However, griffins are more often the attacker than attacked and while both appear in large scale media where they can even be directly associated, griffins were the choice creature as attendants of figures of powers. Nevertheless, a strong analogy of lions and griffins has to be acknowledged for the Late Bronze Age, where both appear as hunters and attendants or protectors (Morgan 1988, 52).

Diana Wolf

References

J. Aruz. 2008. Marks of Distinction. Seals and Cultural Exchange between the Aegean and the Orient (ca. 2600 - 1360 BC). CMS Beiheft 7. Mainz am Rhein (Philipp von Zabern).

F. Blakolmer. 2016. Hierarchy and symbolism of animals and mythical creatures in the Aegean Bronze Age. A statistical and contextual approach. In E. Alram-Stern, F. Blakolmer, S. Deger-Jalkotzy, R. Laffineur and J. Weilhartner,(eds.), Metaphysis. Ritual, Myth and Symbolism in the Aegean Bronze Age; Proceedings of the 15th International Aegean Conference, Vienna, Institute for Oriental and European Archaeology, Aegean and Anatolia Department, Austrian Academy of Sciences and Institute of Classical Archaeology, University of Vienna, 22-25 April 2014. Aegaeum 39. Leuven (Peeters): 61–68.

C. Delplace. 1967. Le griffon créto-mycénien. L'Antiquité Classique 36.1: 49-86.

L. Morgan. 1988. The Miniature Wall-Paintings of Thera. Cambridge: University Press.

A.Shapland. 2010. The Minoan lion: presence and absence on Bronze Age Crete. WorldArch 42: 273-89.

2018

Nov18- Oct. '18 - Summer '18 - Apr. '18 - Feb. '18 - Jan. '18 -

December 2018

Merry Christmas! ... Frohe Weihnachten! ... Καλά Χριστούγεννα!

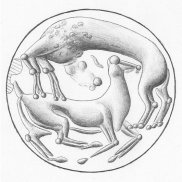

November 2018 (by Diana Wolf)

Lentoid, green jasper. Hard stone technique (cutting wheel, solid drill)

From Mycenae

Stylistic dating: LB I–II

A pair of antithetically recumbent quadrupeds, both looking right, are engraved on the seal face. Below, a wavy incision marks the ground line or a landscape element. The quadrupeds have an elongated body with two rows of horizontal dashes running from the shoulders until the onset of the tail. These bear resemblance to crocodile scales. The creatures’ tails are held high, inclined towards the body in a curve. Their heads sit atop long necks and are comprised of short, pointed ears, an ellipsoid head with a prominent circle for the eye in its center and a long, two-partite snout ending in a short vertical line. A final distinctive characteristic is the quadrupeds’ short legs with broad paws.

Commentary

The quadruped depicted on the seal face is a composite creature conventionally termed 'Minoan Dragon'. Its unparalleled iconography has led to many wild guesses concerning its identity in the early literature, resulting in classifications as a lion, bull, griffin or even crocodile. With the regular appearance of more creatures of this type, scholarship began to recognize it as a distinct fantastic creature. Its name, Minoan dragon, derives from the fantastic ‘Babylonian dragon’, a creature composed of a long body, neck and tail, a horned head and feline forelegs, but taloned hindlegs.

Its origin is difficult to allocate, as it could either have been imported from abroad and re-interpreted according to Minoan ideas or indeed invented in Crete. While it combines elements of animals known from Minoan iconography, such as its dog-like tail or feline haunches, there are many parallels to Babylonian dragons. Another connection to the latter lies in the broader iconographic repertoire: Mesopotamian gods were depicted standing on the back of Babylonian dragons and in several instances, the Minoan Dragon also acts as a mount ridden by an elaborately clad female figure often addressed as the 'Minoan Goddess' (cf. CMS II,6 no. 33, I no. 167, VI no. 321). The creature’s recurrent depiction in an exotic riverine landscape also points toward a foreign origin.

The Minoan Dragon possibly made its first appearance on Crete in the period MM II where it was depicted with combined elements of dog and lion iconography that soon developed the characteristic features of an elongated body and neck, short legs with paws and the upward curving tail. Its iconography, as exemplified by this seal, becomes more stable and standardized by the period LM I, but it remained open to variation and could be rendered in different styles, such as the ‘Talismanic style’ (cf. CMS XII nos. 290, 291). During LBA I-II Minoan Dragons can appear in pairs, which implies that this was not deemed a unique fantastic creature, but rather a ‘species’ of composite beings, just like griffins or Minoan genii. Seldom do dragons engage in any narrative or activity: they are either represented as recumbent or running specimens, sometimes in a riverine landscape setting with papyrus stalks, in pairs, or as the mount of a prominent female. Its repeated occurrence together with these supposedly divine figures demonstrates its belonging to a metaphysical sphere in Bronze Age cognition. The creatures cease to be represented in glyptic by LBA II–III, a period when they were, however, depicted in plaques and combs rendered in materials of high value, such as gold, ivory and glass. Perhaps it was the rather static representational style with which the fantastic creature was connected and possibly its metaphysical connotations that made it an attractive subject for ornamental use as a symbol on the surface of objects within elite households.

References

J. Aruz. 2008. Marks of Distinction. Seals and Cultural Exchange between the Aegean and the Orient (ca. 2600 - 1360 BC). CMS Beiheft 7. Mainz am Rhein (Philipp von Zabern).

F. Blakolmer. 2016. Hierarchy and symbolism of animals and mythical creatures in the Aegean Bronze Age. A statistical and contextual approach. In E. Alram-Stern, F. Blakolmer, S. Deger-Jalkotzy, R. Laffineur and J. Weilhartner,(eds.), Metaphysis. Ritual, Myth and Symbolism in the Aegean Bronze Age; Proceedings of the 15th International Aegean Conference, Vienna, Institute for Oriental and European Archaeology, Aegean and Anatolia Department, Austrian Academy of Sciences and Institute of Classical Archaeology, University of Vienna, 22-25 April 2014. Aegaeum 39. Leuven (Peeters): 61–68.

M. A. V. Gill. 1963. The Minoan dragon. BICS 10: 1–12.

J.-C. Poursat. 1976. Notes d'iconographie préhellenique: dragons et crocodiles. BCH 100.1: 461–74.

Diana Wolf

October 2018

Lentoid, hard stone. Hard stone technique.

Multiple impressions on a stopper (the stopper is also impressed by another seal face).

Animal sacrifice: A bovid in right profile with the front and back legs tied together in an X-configuration lies on a construction which has at least two legs (altar?). A man in the same profile wearing a belt is standing behind the animal and has his arms outstretched towards its rump. Above the animal there is a pair of horns of consecration and three other intelligible elements.

From Malia, Quartier E (Room IV 2)

Context: LM IIIB

Stylistic dating: LM II–IIIA1

Commentary

The animal’s legs are shown in front of the altar; in other examples they are shown behind the altar. In all these cases we could have attempts to show the animal with tied legs lying on one of its sides, in a way known from the Agia Triada Sarcophagus. In another depiction (see impression) the left front and back leg of the animal are shown in front of the altar and the back legs to its back: here, there is a possibility that the animal is depicted lying with its belly on the altar and legs hanging to either side of it tied together to keep it attached to it. If this reading of the image is correct, the surface of the altar must have been narrow enough for the animal’s legs to be tied on either side of it. The MM II image of two agrimia (wild goats) with crossed legs hanging from a pole carried by a man is a good example on how sacrificial animals with crossed legs could have been tied to an object/construction. Altars on which animals are secured with crossed legs always have two legs.

In a further type of animal sacrifice scene the animal is placed with its back or belly on the altar and has outstretched or bent legs that are, however, not crossed. These animals clearly lie on the surface of the table, either on their back or belly with bent legs. These altars usually have three legs, although there are single examples with four and two legs.

Animal sacrifice scenes are rare in Aegean glyptic. They are most popular on LM II-III seals and are most often encountered on hard stone seals (there is one known soft stone example and one cut in glass). Of interest, however, is the fact that a group of MM II seals which are mostly cut in soft stones displays single animals with crossed legs on their seal faces. The crossed legs of these must signify that they are sacrificial animals with tied legs. The rare cases in which a man is depicted with these animals on these early seals could represent the first examples of animal sacrifice scenes in Aegean glyptic.

Maria Anastasiadou

Summer 2018

Happy Aegean Summer!

April 2018

CMS VI no. 102

Eight-sided prism. Agate. Hard stone technique.

Inscriptions of the Cretan Hieroglyphic on all sides.

From ‘Neapolis’.

Stylistic dating: MM II.

Commentary

The seal belongs to the so-called Hieroglyphic Deposit Group. The seals in this group are cut in hard stones and are elaborately engraved. They most often carry inscriptions of the Cretan Hieroglyphic and are multi-facial, mainly four- and three-sided prisms. This eight-sided prism is a singular example of a Cretan Hieroglyphic multi-facial seal.

Since the Cretan Hieroglyphic has not been deciphered the meaning of the inscriptions on the sides of this piece is unknown. It has, however, been suggested that the inscriptions on Cretan Hieroglyphic seals could encode different responsibilities of their users in a hierarchical administrative system. The idea behind this suggestion is that each inscription encodes an administrative responsibility and, therefore, the more inscriptions one prism carried the more responsibilities its user would have and higher in a hierarchical system (s)he would be.

Impressions of this type of seals on ancient sealings are common and have been found in Knossos, Malia and Petras. Because of the large number of impressions of these seals in Knossos, it has often been been suggested that they were produced there. However, seals (as opposed to seal impressions) of this group have not (yet?) been found in contexts in Knossos (here p. 167). Instead, their distribution as we know it today suggests a larger connection with eastern Crete. The recent discovery of a large batch of this type of seals in the Petras cemetery reinforces the idea that seals of this group were 'at home' in the eastern part of the island.

Maria Anastasiadou

February 2018 (Minoan Valentine)

Side (a) of a stamp cylinder. Hippopotamus ivory. Soft stone technique.

Copulating scene (?): Two human figures, seated the one (right) on top of the other. The figures are facing each other with their faces close to one another. In the field there are three motifs, an Y-motif (sistrum?), a C-spiral and an S-shaped motif whose ends end in plants.

On side b are depicted three fish, the one above (or next to) the other.

From Viannos, Crete

Stylistic dating:EM III-MM IA

Commentary

This is a unique scene in the Aegean image repertoire possibly showing two human figures in sexual intercourse. Despite the fact that a fighting scene cannot be totally ruled out, the posture and the way the two figures are combined in the image suggest a rather intimate scene between the two figures. There are no physical indicators of the sex of the figures, so it is possible that humans of different or the same sex are depicted. Cases in which human figures are shown in sexual arousal but without corporeal proximity are rare but not unknown from Aegean glyptic. It has been suggested recently that this is the state in which two male figures are depicted on the bezel of a Late Bronze Age signet ring from Pylos in Messenia (Robert Kohl).

Three more images which can be interpreted as copulation scenes are known from Aegean glyptic, all Minoan and all involving copulating agrimia. Of interest is the fact that in the aforementioned seal from Pylos an agrimi is depicted alongside the two male figures. A LM I lentoid depicting two waterfowls the one above the other has also been seen by some as a possible copulation image but this interpretation cannot be taken as certain because the image could also be read as showing two animals the one behind the other.

Maria Anastasiadou

January 2018 (by Nadine Becker)

Evans' 'Cattle Pieces': The lost signet ring from Knossos and the signet rings CMS II,8 nos 233 and 232

Three sealings with impressions of gold (?) signet rings

Knossos. Archives Deposit (Evans; the CMS gives different findspots for CMS II,8 nos. 232, 233).

Context dating: LM IB/II–LM III

Stylistic dating: LM IB–II (?)

The first impression is lost today and only known through drawings published by A. Evans. The second and third impressions are published as CMS II,8 nos 233 and 232 respectively.

Description

A. ‘Boy leading beast’

The lost impression shows a scene possibly connected to the dairy sector: At the outer right preserved part of the scene a man in right profile is trying to lead a cow/bull in his direction. The animal does not seem to be willing and is turning its head back, gazing in the opposite direction. Its right front leg, the only preserved in the picture, is either shown in a standing or only slightly moving position. This might explain why the legs of the man are even more stilted while trying to pull the animal. Although the outer right part of the impression is badly preserved, the man also seems to turn his head back towards the animal, strengthening the rather fierce action of dragging the animal involuntarily. In the central part of the impression a numeric Linear B sign (variation of 100?/1?) incised in clay is partially visible.

B. ‘The prize ox’ (CMS II,8 no. 233)

Preserved parts of the impression show the head and the upper body of a standing male figure in left profile, obviously supporting himself on a fence. While one arm is bent, he seems to reach out in the direction of a recumbent bull while gazing at him from his resting position. The scene has a quiet intimate and placid character which results from the fact that the two characters show intersecting gazes, they are located close to each other and the man seems to reach out to touch the bull which is neither escaping nor attacking.

C. ‘Boy milking cow’ (CMS II,8 no. 232)

At the outer left part of the preserved impression a man in right profile is slightly bending forward in order to reach the udder of a standing cow. Only the hind legs and a small part of the body of the animal are preserved, but a part of the right horn, visible above the right hind leg, indicates that the animal is actually turning its head back in direction to the man. At the same time, the hind legs and hoofs are shown in a tensed, moving position, probably suggesting that the animal is either struggling to escape the situation or might have been caught by surprise by the man.

Commentary

The gold signet rings known today (98) are outnumbered by the impressions of signet rings that only survive on clay sealings (252). The surviving rings and ring impressions generate a catalogue of 350 so far known unique pieces, each of which represents a masterpiece of Aegean art. As it seems, gold signet rings were ever since valued due to their highly complicated and time-consuming manufacture, but at the same time the rate of reuse of the material must have been very high. This is the reason why gold signet rings and metal seals in general seem to have a quite low rate of archaeological transmission.

As if the loss of the actual rings was not bad enough, some of their impressions got lost in modern times and with them, the knowledge about their existence. The lost impression of the signet ring from Knossos is among those pieces. Together with CMS II,8 nos 232 and 233 the sealing was drawn by A. Evans in his 1902 notebook and then published in The Palace of Minos IV, 2 (1935) in a chapter about the 'Late Minoan Vogue of true "Cattle Pieces"' together with another drawing of a red jasper lentoid. The lost impression is of high importance for enriching our knowledge about scenes of everyday life in Aegean glyptic, as already noted by Evans. Together with the other two rings it highlights several stages of the complex human-animal interaction depicted in bucolic scenes reaching from intimacy (CMS II,8 233) to simple obedience (lost impression).

When coming to the reconstruction of seal shapes, it is certain that the ring that impressed CMS II,8 no. 233 was made of gold: the ellipsoid and elongated outline of the seal face can only have belonged to a metal signet ring. Although the seal shapes of CMS II,8 no. 232 and the lost signet ring were recontructed in a more ‚swaged’ way in the Palace of Minos IV, a possible discoid seal shape can be ruled out. The inclination of the preserved outline and the fact that in both cases large animal bodies have to be complemented leaves no doubt that these impressions were also made by gold signet rings.

Commentary on the imagery of the three sealings

A: The theme ‘man leading animal’ is quite common in Aegean glyptic but the ‘revolting’ of the tamed animal is only rarely shown. A signet ring impression that could be seen as showing two goats revolting against the robbery of their kids is an exception concerning signet ring iconography.

B: The scene is a rare piece of Aegean art showing a peaceful union of a man and a once wild animal not involved in a combat scene, a hunting scene or placed in an antithetical composition. With the exception of an image with a similarly recumbent bull chained up to an altar that shows parallels to the ‘fence’ in this impression, the scene is without parallels in signet ring iconography. Peaceful interactions of humans and animals are sometimes visible in scenes primarily showing seating female deities like the Potnia Theron or the Potnios Theron. Such images are also encountered on several signet rings and signet ring impressions.

C: The cow turning back its head is a well-known motif in Aegean glyptic and is also encountered on signet rings and signet ring impressions. However, milking scenes, which belong to the seldom ‘genre/bucolic scenes’ that show men and women in everyday actions, are extremely rare. Another superb example of such a scene is the ‘bucolic’ scene impressed on a sealing from Chania.

Bibliography

Evans 1935

A. Evans. 1935. The Palace of Minos. A Comparative Account of the Successive Stages of the Early Cretan Civilization as Illustrated by the Discoveries at Knossos, IV, 2. Camp-Stool Fresco, Long-Robed Priests and Beneficent Genii; Chryselephantine Boy-God and Ritual Hair-Offering; Intaglio Types, M.M. III–L. M. II, Late Hoards of Sealings, Deposits of Inscribed Tablets and the Palace Stores; Linear Script B and its Mainland Extension, Closing Palatial Phase; Room of Throne and Final Catastrophe. London (Macmillan and Co., Limited).

Gill 1965

M. A. V. Gill. 1965. The Knossos sealings: Provenance and identification. BSA 60: 58–98.

Popham – Gill 1995

M. R. Popham – M. A. V. Gill. 1995. The latest sealings from the palace and houses at Knossos. BSA Studies I. Oxford (Alden Press).

Dec. '17 - Nov. '17 - Oct. '17 - Summer '17- June '17 - Apr. '17 - Mar. '17 - Feb. '17 - Jan. '17

December 2017

For full HD resolution video see here

3D Animation: Dionyssis Antypas

November 2017

Conoid clay stamp without a stringhole with an impression of the impression of a lentoid (hard stone). The clay is burnt either on purpose or accidentally.

Animal attack scene: A lion in left profile is attacking a hoofed quadruped (bovid?) in right profile. The lion is turning its forepart backwards and steps on the quadruped's back to bite it on the neck.

From Knossos, Palace, Corridor of the Stone Basin

Stylistic dating:LB II-IIIA1

Commentary

The clay was formed in the shape of a conoid and impressed on the impression of a lentoid. This way a stamp with intaglio was created which could be used in place of the lentoid. For this reason, and despite the fact that the stamp was created by impressing, this object can be seen as a seal.

This is a rare attestation of an attempt to create the copy of a seal. The stamp’s conoid shape, its concave sides and the ‘intaglio’ on its base make it appropriate for handling as a seal. However, the fact that it does not have a stringhole means it could not be carried by being hanged on the body. The object could have been created for legal (e.g. need of a duplicate in the administrative sphere) use or represent a successful attempt to counterfeit a seal for illegal use.

Two other conoid clay stamps are known from the Aegean, one from Malia and the other from Knossos, and they could have had a similar function as CMS II,8 no. 362. A fourth clay object with the impression of a signet rings’s impression (here image Pla1) that comes from Knossos looks more like a large nodulus (type of nodule) and would not have been appropriate for use as a stamp. It is probable that in the case of this object, the signet ring that was needed to impress it was not at hand but another nodule with the ring's impression was available (possibly one of these here: images Pla2-4): this impression could have been used to impress the nodulus as a substitute for the signet ring.

Maria Anastasiadou

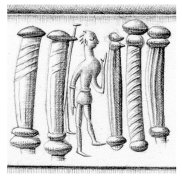

October 2017

Barrel-shaped. Agate. Hard-stone technique.

A man is standing in right profile among five columns, two behind him and three in front of him. The man has short spiky hair combed backwards, one arm down and one arm bent upwards in front of him. He is wearing a belt, a bracelet and, possibly, a short garment around the pelvis. The columns behind the figure have a double base but those in front of him double capitals. The bodies of the columns have relief decoration that could be interpreted as fluting: two have vertical fluting, one spiral fluting, and two spiral fluting on top and vertical on the lower part. A linear element just behind the figure could hypothetically represent an attempt to render a sixth column with a double capital and a single base in the background.

From Mycenae, Chamber Tomb 68

Stylistic Dating: LB II-LB IIIA1?

Commentary

This is a rare representation of a human shown standing in what appears to be an architectural setting represented by columns. The fact that the man has the same dimensions as the columns suggests that the human figure was the centre of interest in the representation and the columns were added as secondary elements, probably in order to suggest a ‘colonnaded’ area in which the figure was standing. The setting could represent an open or closed space. The absence of a roof line does not, however, necessarily suggest that this is an open space but is more probably a practicality connected with the fact that the figure is as large as the columns: if a roof line ahd been rendered on top of the columns, the man’s head would be very close to it and this would make the unnaturally large size of the figure immediately obvious.

Scenes with humans in association with columns are rare in Aegean glyptic. In such scenes, the columns appear as single elements and function more as symbols and less as indicators of architectural settings. The closest parallel to the scene on CMS I no. 107 is the representation of a female figure standing between two columns on a Minoan soft stone seal of unknown provenance. However, the columns here are shorter than the figure and were probably meant to have a symbolic meaning as opposed to a function of supporting a roof.

Barrel-shaped seals are differentiated from cylinder-seals by the fact that they have tapering ends. They are only represented by a handful of examples in the Aegean Bronze Age and date to LB I-IIIA1. Examples of this type of seals come from the mainland, the islands and also Crete.

Maria Anastasiadou

Summer 2017

Happy Aegean Summer!

June 2017

Lentoid. Serpentine/Schist. Soft stone technique.

A bird lady with the head in left profile.

Stylistic dating: LM I

Commentary

The term bird lady describes a Minoan hybrid that stands upright like a human and has features of a bird from the waist to the head and, from the waist downward, the lower body of a woman wearing a long skirt. Most bird ladies stand with their body depicted frontally and their head shown in profile looking to the side or up. There are, however, some bird ladies with their torsos shown in profile and a rare example of a bird lady shown entirely in profile and sitting .

It is not always easy to differentiate between depictions of bird ladies and birds on seals, since the triangular feathered tails of birds can sometimes look like skirts. The decisive criterion for telling bird ladies apart from birds are the legs: if there are legs under the triangular lower part of the depiction, the creature is a bird lady. There are a few cases, however, in which bird ladies do not show legs but are recognized as such by the prominent folds on their skirts. With one exception, whose authenticity may be contested, proper bird ladies do not have female breasts as their torso is that of a bird. Creatures that look like bird ladies but have breasts belong to a different category of hybrids that do not have a standard form but show different elements in each existing version (see here).

25 depictions of bird ladies, most of which are engraved on lentoids, have been published at the CMS. All bird ladies appear on soft stone seals and many are engraved in a rather sketchy manner. Among them, less than a half have a known provenance and only two come from a dated context. The extant examples are, however, dated to LM I on the basis of stylistic considerations.

Since hybrids were part of the metaphysical belief system of the Minoans, their appearance on seals confirms that some seals also had, among others, a protective function for their users. The connection of bird ladies with seals cut in soft local stones and in a sketchy manner is an indication that these creatures were connected with a Minoan folk belief. It is perhaps no chance that some bird ladies are very similar to certain birds on talismanic seals, which are objects that must have had an increased amuletic character.

Maria Anastasiadou

April 2017 (Easter Bunny by Olga Krzyszkowska!)

Stepped pyramid with roughly square seal face. Carnelian: hard stone technique.

A recumbent animal to the left; a series of fine vertical lines in the background.

Armeni Cemetery: chamber tomb 38

Context dating: LM IIIA2–B1

Stylistic dating: MM II

Commentary

In almost every respect — motif, shape, material, and context — CMS V no. 263 is unusual. The motif comprises a recumbent animal, deeply engraved, which occupies virtually the entire seal face, square in shape; surrounding the animal are lightly engraved vertical lines. The animal’s head is formed by a large solid dot; another solid dot represents the eye. The mouth is open, with a dot indicating the nose and a short line for the jaw. Beneath a short but slender neck the animal’s body is rather bulky, with little sign of modelling. The forelegs project from beneath the chest and terminate in simple solid dots. The near hind leg extends from the rump and is bent sharply and rather clumsily to form an unnaturally elongated lower limb, set near the edge of the seal face. Only the lower part of the far hind leg appears beneath the animal’s belly. The tail is held almost erect, curving very slightly. All in all the proportions of this creature are decidedly odd and in no way conform to representations of goats and bulls in the MM II repertoire (or indeed later). But most striking by far are the features projecting at right angles from the head and running parallel with the animal’s back — resembling the elongated oval ears of a rabbit or hare, and not the curving horns of a goat or bull.

While rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) are a west Mediterranean species, probably not brought to the Aegean until the Roman period or later, the hare (Lepus europaeus) appears in the Cretan faunal record from the Middle Minoan period through to the Byzantine era, and indeed is still present on the island today. It is likely that the species was deliberately introduced, since there is as yet no evidence for hare in the fossil (Pleistocene) record. Although hare seem to be ubiquitous, in that they are attested in all parts of the island during Minoan times, the quantity of faunal evidence is slender, with sites often yielding no more than a single bone or two. This is largely explained by the fragility of the bones and post-depositional factors. Nevertheless, one imagines that they served as useful sources of pelts and protein. Yet apart from the single possible representation on CMS V no. 263, hare are entirely absent from the iconographical record. This also applies to other small mammals, such as the badger (M. meles arculus) and the beech or stone marten (Martes foina), both probably present in Crete since the Pleistocene and attested in Minoan contexts.

The seal shape — a stepped pyramid — is highly unusual: only four examples are known. Of these two rather low pyramids, made of bone, are firmly datable by both context and style to the late Prepalatial period, EM III–MM IA (from Gournes and Archanes). A third example (now in the British Museum and said to come from excavations carried out by Sir Alfred Biliotti in Rhodes) is made of either chlorite or serpentine and has a simple design comprising circles and diagonal lines; it is datable to MM II. Although the ‘steps’ of the London seal are now worn smooth, it provides the closest parallel to the shape of CMS V no. 263 from Armeni. Stepped pyramids are normally furnished with suspension holes just below their apex. Originally this also applied to the Armeni seal, but at some point in its life the apex and piercing were damaged and a new suspension hole was provided lower down.

CMS V no. 263 is made of carnelian, but only about one-quarter of the seal displays the typical translucent orange-red hue associated with this material. Virtually the entire seal face, and three sides of the stepped pyramid, are opaque and creamy white in colour. In some areas (though not on the face) patterns of very fine cracking (craquelure), veining or irregular blemishes can be observed, showing up as slightly darker than the cream-coloured ground. These features strongly suggest that at some point the seal was exposed to high temperatures, if not to fire. While similar changes to colour, opacity and structure are often observed on Aegean seals made of agate, carnelian and chalcedony, only limited experimental work been undertaken in controlled laboratory conditions, in order to document the various structural changes involved and length of exposure to heat/fire that they represent.

The seal came to light in chamber tomb 38 in the large Armeni cemetery, south of Rethymnon. Altogether more than 225 tombs have been excavated here, most dating to LM IIIA2/B. Roughly 30% of the tombs contained at least one seal: about 165 were recovered in total, far exceeding the number known from any other cemetery in the Bronze Age Aegean. Another phenomenon observed at Armeni is the high proportion of ‘antique’ seals, which are older — sometimes significantly older — than their context. Roughly 20% are datable to LM I–II or earlier; these include numerous seals in the MM III–LM I ‘talismanic’ style, a MM II–III rock crystal discoid with ‘architectural’ design and even a MM I pierced conoid. It is entirely possible that such antique seals survived by being incorporated into necklaces. Indeed listed among the finds from tomb 38 are beads from a necklace (without further details), along with a sword and dagger (both of bronze) and some eight vases of various shapes. As yet no information exists regarding the number or sex of the burials: further details may become available when the cemetery is finally published.

Irrespective of context date and its many unusual features, CMS V no. 263 can be firmly dated to MM II. Although only one other stepped pyramid of this date exists, the concept fits well with the popular loop-handled seals or Petschafte, common in this period. Carnelian and other semi-precious stones made their appearance in MM II and were invariably engraved with rotary technology, also introduced in this period. The motif, however, is truly unique. The vertical lines in the background are unparalleled: while they may be no more than horror vacui, they might be construed as indicating an enclosure or fencing of some kind. The animal has no parallels whatsoever among depictions of sheep, goats, pigs, bulls, or deer in MM II or later, and indeed the proportions are entirely wrong for ungulates. It is, of course, conceivable that the engraver simply made a series of miscalculations regarding the space needed to execute the design and to incorporate curving horns. But MM II was a period of great experimentation in Aegean glyptic, not only in respect of technique, but also in the expansion of the iconographic repertoire. Cats and deer, perhaps first introduced to the island in MM II, now make their first appearance in the glyptic record, as do exotic Mischwesen (griffins, sphinxes and the Minoan genius). The long ears, and for that matter the elongated hind leg of the creature depicted on CMS V no. 263, undoubtedly conjure up the notion of a hare. Whether by chance or design remains an open question.

References

Krzyszkowska, Olga. 2011. Seals and society in Late Bronze Age Crete. In: Πεπραγμένα Ι′ Διεθνούς Κρητολογικού Συνεδρίου A1, 434–48. Χανιά: Φιλολογικός Σύλλογος «Ο Χρυσόστομος»

Krzyszkowska, Olga. 2014. Cutting to the chase: hunting in Minoan Crete. In George Touchais et al. (eds.), PHYSIS: L’environnement naturel et la relation homme-milieu dans le monde égéen protohistorique, 341–47. Aegeum 37. Leuven: Peeters.

Masseti, Marco. 2012. Atlas of Terrestrial Mammals of the Ionian and Aegean Islands. Berlin/ Boston: De Gruyter, esp. 49–59.

Moody, Jane. 2012. Hinterlands and hinterseas: resources and production zones in Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Crete. In: Gerald Cadogan et al. (eds.). Parallel Lives: Ancient Island Societies in Crete and Cyprus, 233–71; esp. 246–47. BSA Studies 20. London: British School at Athens.

Yule, Paul – K. Shurman, Technical observations on glyptic. In: Ingo Pini (ed.), Studien zur Minoischen und Helladischen Glyptik. Beiträge zum 2. Marburger Siegel-Symposium 26.–30. September 1978, 273–82. CMS Beiheft 1. Berlin: Gebrüder Mann.

Images

Colour images by Olga Krzyszkowska. Copyright: Olga Krzyszkowska.

Olga Krzyszkowska, Institute of Classical Studies, London

March 2017

Seal impression of a soft stone (?) lentoid on two two-hole handing nodules

A human forearm wearing two bracelets in left profile is shown holding a large lily.

From Knossos, Palace, Queen’s Megaron

Stylistic dating: LM IB

Commentary

The forearm starts at the edge of the seal face, an artistic convention which is used to suggest that the representation is part of a larger image, that of a human holding a flower. The representation on this face is then, literally, a Minoan close-up.

Images of humans holding flowers are only encountered on a few Aegean seals. All these seals are cut in precious materials, i.e. metals and hard stone, and in all cases the flowers are held by female figures. Most figures in these images hold lilies but one is also depicted holding a papyrus, another poppies and a third an unidentifiable flower. The motif of a woman holding flowers seems to be connected with the sphere of the ritual since most of the images in which the motif is encountered also contain symbols that are well-known from the Minoan ritual, such as horns of consecration, the sun and the moon, and a monkey holding a basket.

Close-up images are rare but not unheard of in Aegean seal imagery. The first image that can be identified as such is the EM III/MM IA depiction of four ‘parading’ lions whose rumps end at the edges of the seal face. The presence of the animals' hind legs is suggested but the legs themselves are not depicted. In MM II there is a rare representation of the protome of an agrimi and that of the intricate forepart of a deer whose neck and waist respectively end at the edge of the seal face suggesting that the body continues. In the Late Minoan period, there is a larger variety of representations that can be interpreted as close-up images. These are the depictions of animal protomes ‘cut’ at the shoulders, boats whose one half is omitted, humans walking in front of friezes which end at the seal face’s edge and animals in a landscape that seems to continue beyond the seal face edges. In the Early Bronze Age, ornamental rapport patterns which cover the whole of the seal face may also be seen as close-up views of larger ornamental patterns.

Maria Anastasiadou

February 2017

Round flat seal face, soft stone. Soft stone technique.

Three impressions on a direct object sealing.

A standing man and a standing woman in profile are facing each other. The woman has shoulder long hair and wears a long chequered skirt/dress. A short vertical line is engraved between the faces of the figures and a branch motif is seen upside down behind the head of the female figure.

From Phaistos, Palace, Room 25

Context: MM IIB

Stylistic dating: MM II

Commentary

The arms of the figures are hanging either side of the body. The left arm of the male and the right arm of the female figure are abutting at their edge, as if the two figures were holding hands. It is not certain whether this is intentional or came about by chance due to the restricted space on the seal face, which has a diameter of just 1,15 cm. Irrespective of this, the image creates the impression of intimacy between the two figures because they are facing each other, and possibly, looking at each other.

Men and women are occasionally combined in one image on Aegean seals. In the vast majority of cases, the images in which male and female figures are encountered together show some connection with the sphere of the metaphysical. In an image that could represent an excerpt from a Minoan story for example, a male figure is holding the hand of a female figure in front of a dinghy. A small female figure floating in the sky above the dinghy suggests that this scene is in some way connected to the sphere of the religious. In another occasion, a standing male extends the arm to that of a large female figure who is depicted seated opposite him. A small seated figure is floating above the arm of the male figure and could, in a bold interpretation, perhaps be read as a toddler in what would then be a rare occasion of straightforward (as opposed to symbolic) expression of fertility veneration. The iconographical vocabulary of the image, e.g. the seated female figure and the dotted line floating in the sky, which are often encountered on scenes with a religious character, would also suggest some connection with the metaphysical.

More, at least seemingly, mundane depictions of the two sexes are rare on Aegean seals. Apart from the Phaistos image, a unique representation on a prepalatial stamp cylinder appears to depict sexual intercourse between two figures (man and woman?). On another occasion, a male and a possibly female figure (long skirt) are depicted either side of a tripod vessel. The figures are holding a linear element in the interior of the vessel in what could conditionally be seen as a scene of food preparation. In a signet ring from Tiryns, two pairs of a male and a female figure are shown interacting in front of a ship.

Maria Anastasiadou

January 2017

Image c: Flat ellipsoidal seal face, soft stone. Soft stone technique.

Image d: Most probably the backside of a soft stone seal with undulating back.

Numerous impressions on the surface of a direct object sealing that was fastening a lid made of bast to the mouth of a pithoid vessel. The sealing, which has been preserved in fragments, formed a circle by lining the mouth of the vessel. Depicted here are a fragment of the sealing (image b) and two silicon imprints of four of the impressions (images c, d).

Image c: An outline ellipse is divided in two by a line which runs along its major axis. Two dots sit antithetically on the form’s outline.

Image d: No motif.

From Malia, Quartier Mu, Building A (Room III 17)

Context: MM IIB

Stylistic dating: MM IIB

Commentary

The seal impressions are scattered on the whole surface of the sealing. Since the seal was small and the diameter of the vessel’s mouth much larger, the seal was impressed many times on the surface of the sealing. This was an attempt for the lid of the vessel to be secured better from unauthorized opening: if no part of the sealing stays without a seal impression, no part of it can be broken and mended again without the party authorised to the contents of the vessel noticing.

Half of the sealing is impressed with a seal face and the other half with what seems to be the backside of a seal. In both cases, the edge of the seal user’s thumb or index finger has been impressed next to the seal along one of its long sides (images c, d). If it is assumed that there was only one seal user, a hypothetical reconstruction of the events that resulted in the sealing carrying impressions of two different surfaces is the following: The seal user was using the seal to impress the sealing when, at about halfway of this process, the process was interrupted. When work was resumed, the seal was grasped without much thought or checking that it was being held correctly. As a result of this and probably without the seal user noticing, the seal was impressed on the remaining half of the sealing with the backside instead of the seal face. If this version of the events is correct, it would mean that the process of sealing was taking place mechanically without much attention to the quality of the impression. Recognizing the seal face in the impression would have been less important than the act of sealing itself which is what would have provided a guarantee that the contents of the vessel were untouched.

The maximal length of the finger edges is 1.29 cm (edge next to the seal face) and thickness 0.63 cm (edge along the backside of the seal). In one of the casts kept at the CMS Archive, the edges of both the thumb and the index finger between which the seal was kept can be seen either side of the seal. The seal face finds no good stylistic parallels but its (?) backside provides a good hint for dating: this was a foliate back, a seal shape which is dated to MM II.

Maria Anastasiadou

Dec. '16 - Nov. '16 - Oct. '16 - Summer '16 - June '16 - May '16 - Apr- '16 - Mar. '16 - Feb. '16 - Jan. '16/Dec. '15 -

December 2016

November 2016

Round convex seal face, soft material. Soft stone technique.

Impression on a flat-based nodule

Three hands are placed the one above the other directed alternatingly to the left and to the right. The thumb is separated from the other fingers with are stretched to the front. Around the wrists there are double bracelets in the form of wavy lines.

From Kato Zakros, House A, Room VII

Context: LM IB

Stylistic dating: LM I

Commentary

Depictions of hands are rare in Minoan seals and when encountered, they are most often found on seals that date to the Middle Minoan period. The best parallel to the Kato Zakros hands is the depiction of a hand in front of interlace motif engraved on a seal face impressed on a sealing from Knossos. A hand with four fingers is seen on one side of a seal connected with the so-called Archanes Script. Hands on Middle Minoan II seals function as signs of the Cretan Hieroglyphic.

A magnificent find from Akrotiri may help understand the Kato Zakros hands better. This is a wooden (!) set of two small hands which have been uniquely preserved in the layer of volcanic pumice and ash of the Late Cycladic I settlement (Mikrakis 2007, 90). The objects represent a right and a left hand, each of which wears double bracelets on the wrist and has a hoop instead of a forearm. The Akrotiri hands have been interpreted convincingly as a pair of clappers meant to be held in between the fingers of one hand and be clapped against each other in a way similar to that in which castanets are used today. The Kato Zakros hands then, could also be depictions of similar musical instruments as opposed to those of actual human hands.

Harps, phorminxes, sistrums and triton shells used as trumpets are further examples of musical instruments depicted on Aegean seals. Most impressive though is the image of two human figures that could be interpreted as playing music using a syrinx- and two drum-like instruments!

Maria Anastasiadou

October 2016

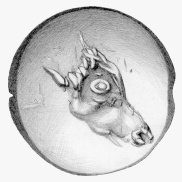

Amygdaloid. Hollow gold. Engraved by hand, punched, granulation around the stringholes.

A hunting scene: A large bull is depicted in right profile with the neck and head turned to the side and downwards. The animal is tangled in a net that extends over its forepart and forces it into the contorted pose. A right-facing human figure with its body bent backwards in a U-configuration is depicted in the foreground between the animal and the rocky ground. A tree can be seen in front of the animal and a patch of the rocky landscape (?) hanging from the upper part of the image.

From Routsi Myrsinochoriou (Messenia), Tholos tomb 2, Shaft 2

Stylistic dating: LB I-II

Commentary

The bull is large and bulky occupying the larger part of the seal face and outsizing all other elements of the composition. The size of the animal underlines its strength and emphasizes the feat of the human figure in managing to capture it. The image conveys strength and intense movement because of the powerful musculature of the two creatures and their highly animated bodies. The acrobatic posture of the human figure and its placement near the animal’s horns bring to mind bull-leaping scenes.

This seal finds a remarkable parallel to the 'violent' Vapheio Cup (here up). The seal is made by a golden sheet that was engraved and punched. Punching is a technique similar to the one used for the creation of the relief of the Vapheio Cup. More importantly, the bull-hunting scenes on the two artifacts demonstrate striking similarities. They both share the themes of enforcement of a bull into a contorted pose by a capturing net, a small tree in front of the animal, acrobatic posture of the capturers and a rocky landscape. The image on the seal may involve one and not three animals as is the case with the Vapheio Cup image but it combines around this bull several elements that are 'divided' among three bulls in the Vapheio Cup: the captured animal, the human figures and the rocky landscape.

It is possible that both the cup and the seal were made in metal-working workshops specializing in the production of metal luxury artifacts. Such workshops would probably not have worked on objects made of stone, such as stone seals.

Maria Anastasiadou

July/September 2016

Happy Aegean Summer with Minoans on the sea!

This seal face is not published at the CMS. A farmer found this seal, a MM II three-sided steatite gable, in Malia and showed it to the French archaeologists Pierre Demargne and Fernard Chapouthier in the summer of 1932. Chapouthier prepared drawings of the piece on the spot and Demargne went on to publish these drawings and a treatise on the piece. The seal is now lost, it is possible that it is still in the hands of a Maliote family or that it has ended up in some private collection.

For more information and images of the piece, see Demargne, Pierre. 1939. Le maitre des animaux sur une gemme crétoise du MM I. In: Mélanges syriens offerts a monsieur René Dussaud par ses amis et ses élèves I, 121-127. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. For the drawing reproduced above, see ibid. 122 Fig. 1.

Back with our monthly seals and more news on seals in October!

Maria Anastasiadou

June 2016

Announcement

We are very glad to announce that the CMS Heidelberg received funding from the DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) for the publication of a new CMS volume!

The new project will have an international orientation and will be carried out in English. It will rely on close collaboration between the University of Heidelberg, the excavators of the seals, the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion and the Greek Ministry of Culture.

Starting after the summer 2016!

May 2016

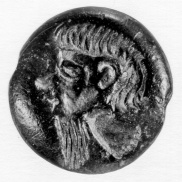

Two-sided lentoid. Soft stone. Soft stone technique.

Side a: The head of a man in right profile. The hair of the man is short in front and longer at the back (mullet). The man has a long beard which grows only from the chin. Side b: The head of a bovid in right profile.

Stylistic dating: MM III-LM I?

Commentary

The face of the man (side a) finds several parallels on early neopalatial seals cut in soft and hard stones. These faces either have no beard or they have a beard growing from the chin and rarer, from the chin and the cheeks. Mustaches are not attested in these cases.

It has been suggested that some of these faces could represent real portraits of specific individuals. Arthur Evans had even seen in two heads from Knossos (seal impressions on nodules) the portraits of a Minoan dynast and his son. Much discussed has been the head engraved on a small amethyst lentoid from the shaft graves of Mycenae which has been described as the portrait of a Mycenaean chieftain. However, most scholars today agree that all these images are idealized versions of faces and do not reproduce the characteristics of specific men (see for example, Pini here). Moreover, the Mycenae seal is now seen as a Cretan product.

Soft stone discoids and lentoids with heads of men belong to a small group of seals with soft intaglios and plastically rendered motifs. Apart from heads of men also engraved on these seals are animal heads and animal protomes. The seals of this group were produced in or near Knossos in the early neopalatial period.

Maria Anastasiadou

April 2016 (by Nadine Becker)

Signet ring. Gold. The motif is created by embossing and engraving, the ring by soldering and hammering.

Three female figures wearing flounced skirts and holding branches (as offerings?) approach a structure (altar?) placed in the left side (bezel) of the composition.

From Mycenae, Chamber tomb 55

Stylistic dating: LH II/IIIA1 (Nadine Becker)

Commentary

The image of female figures approaching a cult structure is quite common on signet rings. However, not only these motifs but also preliminary sketches can be seen on the bezel of this ring (marked black in image 3). This is a rare but particularly interesting trait.

The sketches provide clues regarding the ways in which signet rings were engraved and the details of the planning involved when engraving complex compositions on small-scale image carriers. In the ring in question, a horizontal line that was supposed to represent the ground was incised first. However, this was later substituted by another line lower in the field which left more free space for the engraving of the three figures. The feet of these figures can now be seen clearly engraved over the first line. Similarly, the contour lines of the figures were initially sketched further to the left (bezel) but in the final stage of the engraving process they where cut further to the right. As a result of this, the preliminary sketches of the raised arm of the first figure are now clearly visible directly above the altar, those of its torso and skirt to the right of the altar, and that of its hanging arm to the left of this arm. Other short lines closer to the second and third figure must also constitute preliminary sketches. The decision to shift the center of the group of the female figures to the right was probably related with the fact that their initial positioning did not leave enough space for the altar.

Several signet rings display incised lines which constitute either preliminary sketches or helping lines for estimating the space available for each motif within the composition. Lines of this kind have not been looked at in detail by Aegean scholars but have been noticed in the past (most notably by Walter Müller [notes at the CMS archive] and Sidney Carter [2000]). The topic is dealt with at length by the author in a publication in preparation (Becker 2015a).

Technical characteristics: The bezel of the ring measures 2,27 x 1,55 cm and the hoop has a diameter of 1,39–1,7 cm. The ring weights 8,5 g (National Archaeological Museum Athens). X-ray and ultrasound examination of the ring revealed a gold content of 70,4 % (27,9 % Ag, 1,7 % Cu), which is a rather low percentage of the metal (Müller 2003, Table C). The bezel is hollow (type III signet ring) and the hoop displays a narrow central row put together by partly overlapping discs (type IV h in Becker 2015b, Table 2). Rings with hoops of this type have only been found in LB II–III contexts in the mainland (e.g. CMS I 87; 189 [the latter from a LH IIIA1 context: Persson 1931, 3–18]).

Context: The tomb in the lower town of Mycenae in which the ring was found is not published (for other tombs from the same necropolis, see Tsountas 1888, 119-180). Therefore the burial context (pottery, grave goods, number of inhumations) is unknown.

References

| Becker 2015a | Becker, Nadine. 2015. Die goldenen Siegelringe der Ägäischen Bronzezeit. Untersuchungen zu Form, Funktion und sozialer Signifikanz eines bronzezeitlichen Prestigeobjekts I-II. Ph.D. diss., University of Heidelberg. |

| Becker 2015b | Becker, Nadine. 2015. Attribution Studies of Golden Signet Rings: New Efforts in Tracing Aegean Goldsmiths and their Workshops, AEA 11, 73–88. |

| Carter 2000 | Carter, Sidney Wood. 2000. ›The Battle of the Glen‹ Revisited: A Gold Signet Ring (CMS I 16) of the Aegean Late Bronze Age in its Full Iconographic Context. Unpublished Senior Honors Thesis in the Department of Classics, Dartmouth College. |

| Müller 2003 | Müller, Walter. 2003. Precision Measurements of Minoan and Mycenaean Gold Rings with Ultrasound. In: Karen Polinger Foster (ed.), Metron. Measuring the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 9th International Aegean Conference / 9e Rencontre Égéenne Internationale, New Haven, Yale University, 18–21 April 2002, 475–481. Aegaeum 24. Liège: Univ. de Liége, Histoire de l'Art et Archéologie de la Grèce Antique. |

| Persson 1931 | Persson, Axel W. 1931.The Royal Tombs at Dendra near Midea. Lund: Gleerup. |

| Tsountas 1888 | Tsountas, Christos. 1888. Ανασκαφαì τάφων έν Μυκήναις, AEphem, 119–180. |

March 2016 (in collaboration with Hubert Mara)

Signet ring. Gold. Engraved by hand, punched.

A cult scene: A seated female figure in left profile is facing four Minoan Genii in right profile depicted the one behind the other. The female figure is wearing a long garment and possibly a head cover and has waist-long hair. It sits on a chair (throne?) and has its legs on a footstool with handles (?). Behind the chair is depicted a bird in left profile with head turned to the back. Under the bird there is an architectural element with a triglyph frieze. The figure is holding a high conical vessel with the left arm and has its right arm resting on its thigh. Between the female figure and the first Genius there is a short column, behind each Genius a plant-motif. Each Genius is holding a jug with the front legs. The ground is rendered with alternating rows of short vertical parallels and a triglyph frieze. Above the scene, a dotted area (sky with stars?) is defined by a wavy contour. A crescent and a star within a circle possibly stand for the moon and sun. Four motifs in the shape of ears of grain also float in the dotted area.

From Tiryns, House in the Lower Town

Stylistic dating: LB II

Commentary

The vessel held by the female figure is probably a rhyton (a vessel with a hole at the base meant for libation rituals). The Genii hold the jugs with one paw under the base and the other on the top of the handle as if they are ready to pour liquid into the rhyton. Minoan Genii are often depicted holding jugs and have been characterized as libation pourers (p. 217). A famous libation scene in which Minoan Genii take part is carved (in relief) on the body of a LM I stone triton from Malia. Apart from the Tiryns ring, other cases in which Minoan Genii are combined with a female figure are two seal impressions from the Helladic mainland, one from Thebes (p. 94) and another from Pylos. The ring stands out not only on account of its complicated composition but also its size. The length of the bezel exceeds 5.5 cm and the diameter of the hoop 2.9 cm. This extraordinary size would not facilitate daily wearing and suggests that this piece was an important status symbol.

The project of the CMS in Marburg (1958-2011) perfected the documentation method of Aegean seals by use of high quality photographs, modern seal impressions and accurate hand drawings. Experimentation with new digital technologies may allow faster documentation of the material. It is, however, a challenge to achieve as accurate results with digital technology as those produced by the human hand.

The first and second image shown here are the CMS drawing and plasticine impression of CMS I no. 179 (Marburg). The third and fourth images are scans made with a high-resolution close-range 3D-scanner (AiCON/Breuckmann) from the seal impression (Heidelberg). The images were rendered with the GigaMesh software framework which is used to improve readability of script in 3D like cuneiform tablets or medieval Hebrew inscriptions. The third image uses a technique called Non-Photo-Realistic (NPR) rendering which applies different amount of hatched lines depending on the (virtual) illumination. Additional outlines are computed shown as thick black lines. The number of colors (levels of gray) is reduced to five, which is known as roon shading. This results in an image similar to a pencil drawing with just a few mouse clicks. The fourth image shows the surface of the sealing mimicking metal, which provides a maximum of contrast.

Maria Anastasiadou – Hubert Mara

February 2016

Rectangular plate with four seal faces. Soft stone technique.

Face c: A dog in contorted pose. The head, neck, legs and rump are shown in profile, the forepart of the body possibly en face (chest). The front legs are splayed either side of the body.

Reported to have been found in Malia

Stylistic dating: MM II

Commentary

The body of the animal is bent in a circle. The pose is unique in Minoan glyptic. It is possible that the engraver was trying to depict the animal lying with its back on the ground in a way similar to that in which the Knossian puppy above is lying (photograph: Stefanie Tuppat).

Dogs with contorted bodies are frequent in Middle Minoan (MM) glyptic but they are most often shown with the rump and back legs rotated 180°. This pose is probably an attempt to depict the animal lying on the ground with its front legs stretched forwards and its back legs to the side. Dogs in similar poses are also seen on the lids of two (earlier) soft stone pyxides, one of which comes from Mochlos and the other from Kato Zakros. In MM II animals in this type of contorted pose (front legs stretched to the front) are encountered on steatite (or rarer hard stone) prisms associated with Malia and eastern Crete. It is probably no coincidence that the two pyxides with dogs in the same pose come from sites in the eastern part of Crete.

CMS VI no. 25 belongs to the MM II Malia/Eastern Crete Steatite Group and could well have been produced in Malia or its environs. The imagery of this seal is elaborated and shows certain progressive elements. Apart from the unique attempt to depict a dog lying on its back, the depiction of a man with feet pointing inwards on one narrow side of this seal is probably an attempt to depict a frontal figure. The unique depiction of a man carrying two agrimia in a pole is engraved on another side of this seal.

Maria Anastasiadou

Dec.'15/Jan. '16 - Nov. '15 - Oct. '15 - Sept./Aug. '15 - July '15 - June '15 - May '15 - Apr. '15 - Mar. '15 - Feb. '15 - Jan. '15/Dec. '14

December 2015 / January 2016

November 2015

Ring stone (unperforated). Cornelian. Hard stone technique.

A lion in right profile standing upright on its back legs is biting the neck of a hooved quadruped standing in front of it in the same profile and posture. The latter has a long neck which is bent 90° to the back. A Π-shape is created by the combination of the bodies of the two animals. In the field are engraved five Greek letters: Μ, Α, Ν, Κ, Λ.

Reported to have been found in Milos

Stylistic dating: not Aegean

Commentary

The Greek letters have been engraved on the seal face with direction left-to-right. This suggests that the motif was meant to be read directly from the seal face (and not its impression).

The seal shape, stylistic considerations (static as opposed to flowing forms) and the Greek letters speak against an Aegean origin of the piece. The composition on the other hand, brings to mind compositions encountered in animal attack scenes on seals of the Late Bronze Age. Margaret Gill has suggested that this seal is a 19th century imitation of an Aegean piece (CMS XI, pp. XXII, 335).

Gem engravers of the 18th and 19th centuries often copied or were inspired by ancient Greek and Roman seals. The seal was bought by the State Hermitage Museum in 1865 and therefore before Schliemann’s discovery of Mycenae and Tiryns (after which artifacts could be recognized as products of the Aegean Bronze Age). Therefore, if this seal is a 19th century product inspired by an Aegean seal it is almost certain that the engraver would not have identified its prototype as Aegean. The piece has a twin to another ring stone kept in the same collection. The two pieces were probably made together.

Maria Anastasiadou

October 2015

Lentoid, steatite. Soft stone technique

Two human figures in profile wearing aprons are depicted either side of a lion which is lying on its back. The upper body of the left figure is bent forwards and down towards the animal, its arms are bent at the chest and one leg is bent in front as if stepping on the animal. The right figure, which has breasts and can thus be identified as a female, has arms extended to the front.

Unknown provenance

Stylistic dating: LB I/II