Lets talk seals!

For the next months, this column will regularly present one by one the most prominent style groups of Aegean seals. The term 'style group' is used here to refer to groups of objects that display the same stilistic traits (iconography, engraving technique, engraving style, materials). The seals of each group date to the same period and must have been manufactured at workshops active in the same cultural mileau. Each group sheds light at different aspects of the Bronze Age Aegean, contributing to a better understanding of issues pertaining, among others, to: the social structure of Aegean societies; the cultural/administrative/political geography of this region in prehistoric times; interregional movements/contacts; and the 'historical' developments in that area and period.

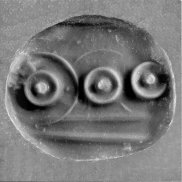

The Talismanic Group

This is the largest group of Aegean seals, counting more than 900 examples. Most are made in hard stones but there are also some soft stone examples. Carnelian and amygdaloids are common. The motifs of these seals are mostly representational; among them are crabs, goats, birds, sprays, amphorae and even sailing ships. The motifs are put together of rapidly executed lines, dots, circles and crescents that are not modelled in forms; tool marks are not smoothed away. As a result, the depictions have a schematic appearance.

Talismanic seals are found throughout Crete and, in lesser quantities, in the Greek mainland. They are especially popular in east Crete and some view them as the Neopalatial successors of the Protopalatial Malia/Eastern Crete Steatite Group and the Hieroglyphic Deposit Group.

Arthur Evans, the excavator of the Knossos palace, defined and named the group. He viewed motifs like the vessels and sprays as having a religious significance, considering them indicative of an amuletic or talismanic function of these seals. Modern seal research suggests caution with the attribution of a magical character in Talismanic seals as clear evidence for this interpretation is missing. However, it is true that such seals were rarely used for sealing purposes — there are only a few ancient impressions from such seal faces. This could support the hypothesis that they were made less for sealing and more for wearing, that is that they were mainly perceived as jewels, status or religious symbols, or even amulets or talismans.

Maria Anastasiadou

Sources/Suggestions for further reading:

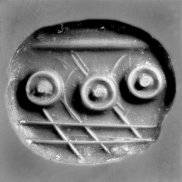

The MM II/III Mesara Stamps

These stamps are only known by their impressions on clay. Their faces differed from those of the typical Aegean seals in that their motifs were not rendered in negative but in positive; as a result, in the impressions they are seen in negative. Moreover, there is no field around the motifs, their contour coincides with that of the seal face.The stamps were probably made of metal — they compare well to a class of Bronze Age copper alloy and bronze seals from the Iranian plateau (for images, see here, pp. 95-97, figs.27-28).

Such stamps were usually impressed on the walls of vessels, probably for decorative and/or symbolic purposes. They are, however, most widely known by their use in the Phaistos Disc, a clay disc with probable inscriptions on its two faces which have been created by using this type of stamps. No sealings with impressions of such stamps are known, which could mean that these objects were not employed as administrative instruments.

.

The use of this type of stamps was widespread in Phaistos, which was probably the centre of their production; significant numbers of specimens are are also known from other Mesarian sites as well as Knossos. The popularity of these objects for decorating vessels in Protopalatial Phaistos attests to a practice indigenous there. This, consequently, confirms the Phaistian character of the Phaistos Disc in which stamps of the same type were also used and which must have been locally manufactured in MM IIIA.

Maria Anastasiadou

Sources/Suggestions for further reading:

The Central Crete Ornamental Group

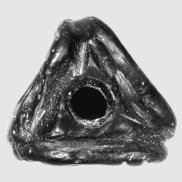

Characteristic are the exclusively ornamental motifs of these seals, which are put together by centred circles, dots and lines. The soft local steatite is common in their manufacture but soft whitish materials, for example man-made paste, are also attested. Three-sided prisms, discoids and Petshafte are popular seal forms.

These objects are popular in the area around Knossos and in the Mesara. Some were possibly produced in the Knossian port settlement Poros-Katsambas, where an artisan's quarter with, among others, jewellery and seal workshops has been excavated. Seals of this group have impressed some sealings from Vano 25, a room associated with the magazines of the Phaistos Palace.

Together with the Mesara Chlorite Group, where ornamental and floral motifs prevail, these seals connect the Protopalatial glyptic of central Crete with ornamental tendencies. Both groups come in stark contrast with the Protopalatial seal groups of eastern central and east Crete, where representational images and inscriptions of the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script are more popular. The prevalence of ornamental motifs in the Protopalatial seals of central Crete possibly suggests that, contrary to what was to follow in the Neopalatial period, figural art played a lesser role there in this earlier phase. Furthermore, the absence of Cretan Hieroglyphs from these seals could indicate that this script was not indigenous in the central part of the island.

Sources/Suggestions for further reading:

Maria Anastasiadou

The Mesara Chlorite Group

These seals are engraved by hand tools and mostly made of chlorite. Among the most common shapes are three-sided prisms, buttons and bottles with round or rarer slighly ellipsoidal seal faces. Radial and rotating ornamental as well as floral motifs arranged with reference to the center of the seal face are popular. Representational motifs are restricted, usually showíng single animals like hoofed quadrupeds and scorpions.

The find spots of these objects are concentrated in the Mesara Plain, where their workshops must have been located. Several seals of this type were used to impress sealings from Vano 25, a room associated with the magazines of the Phaistos Palace. This means that these seals had an administrative function and their users had transactions with the palace.

In contrast to the Protopalatial style groups of east central and east Crete (e.g., Malia/Eastern Crete Steatite Group, Hieroglyphic Deposit Group), these seals do not display inscriptions of the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script. This fits the evidence for the distribution of scripts in Protopalatial Crete, as Linear A and not the Cretan Hieroglyphic is used in the Protopalatial Mesara. It shows that the Mesara seals belong to a separate cultural tradition than the other two style groups, one that is associated with the use of Linear A and did not employ seals as script carriers.

Sources/Suggestions for further reading:

Maria Anastasiadou

The Hieroglyphic Deposit Group

This group encompasses seals engraved in hard stones that are intensively connected with the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script. It takes its name from the so-called Hieroglyphic Deposit of Knossos, an assemblage of Cretan Hieroglyphic documents discovered in the palace of Knossos. As several sealings from this deposit were impressed by seals of the group, the latter was named after the former.

Green jasper, cornelian, agate and chalcedony are often used. Three- and four-sided prisms are common forms but Petshafte are also encountered. The intaglios are deep but have smooth surfaces as they are engraved with the horizontal spindle. Apart from incsriptions of the Cretan Hieroglyphic, other images involving, e.g., humans or human-like heads, cats or their heads, goats and ornamental motifs, are also attested. The group encompasses more than 120 specimens.

Despite the recovery of their impressions in Knossos, these seals cannot be connected with Knossian workshops as most have a reported provenance from find-spots in east Crete. Several specimens have recently been excavated in the cemetery of palatial Petras, near the town of Siteia.

These seals were more intensively used for sealing than their steatite counterparts. Their restricted numbers, precious materials, elaborate engraving technique and access to the technology of script mean they were exclusive objects. It is possible that they were perceived both as administrative instruments and as status symbols.

Sources/Suggestions for further reading:

Maria Anastasiadou

The Malia/Eastern Crete Steatite Group

This is the largest group of Protopalatial seals, counting more than 700 specimens. Typical traits are the use of steatite, the popularity of three-sided prisms (80% of the seal shapes), the deep hand-engraved intaglios and the summarily rendered motifs. Images involving representational motifs, e.g., humans, quadrupeds, spiders, vessels and ships are popular but floral and ornamental motifs as well as inscriptions of the Cretan Hieroglyphic are also encountered.

More than a hundred seals of the group were recovered in the Seal-Cutter's Workshop in Malia. This is one of five workshops of the Quartier Mu, an administrative complex situated 140 m to the NW of the Malia palace. The seal workshop is of great significance for understanding organisational aspects of the Minoan craft of seal engraving. The working space was situated in the upper floor of the two-storey house of the craftsperson and their family. Among its production were specimens of skilled craftsmanship but also pieces attributed to the hands of an apprentice, called by the excavator 'le gâcheur' (the botcher). The production of seals in a complex neighboring the palace could suggest control of the craft from a central administration.

The seals of the group were popular in the town of Malia, which was probably their main center of production, and in sites around it, especially in the Lassithi Plateu and the general region of the Pediada. Clusters of finds from sites in east Crete suggest a familiarity with these objects there. The seals of this type were rarely used in sealing administration, such that main function as some kind of amulets is possible. Since many were produced in the heart of the Malia town, it is possible that outside it they functioned as symbols of ideological connection with it.

Sources/Suggestions for further reading:

- O. Krzyszkowska. 2005. Aegean Seals: An Introduction. London (Institute of Classical Studies): 92–95.

Maria Anastasiadou

The Group of the White Pieces

The group takes its name from the soft whitish material of most pieces. This is possibly some kind of man-made paste consisting of pulverised talc mixed with a binding agent and heated to harden (Krzyszkowska 2005, 73). A few steatite seals, some of which were possibly covered with a whitish coat, also belong to the group.

A large variety of seal shapes are attested, e.g., seals in the form of animals as well as half-ovoids and plano-convex seals with decoration at the backside. The motifs are engraved with hand tools and they are, with very few representational exceptions, floral and ornamental. Quatrefoils, leaves and hatched triangles constitute some of the commonest motifs.

The largest concentration of these seals is noted in south Messara and the region of the Asterousia mountains. The workshops for the production of most pieces were probably located in these areas.

White Pieces in the form of scarabs were inspired by Egyptian scarabs, which were circulating in Crete in the late Prepalatial Period. These Minoan scarabs were influenced by the Egyptian ones not only in shape but also in their material: by using an artificial paste, they made use of a substance comparable to that used for the manufacture of the Egyptian specimens. However, this technology was not only used for scarabs in the White Pieces but was also extended to many clearly Minoan shapes. It is, thus, possible to speak here of 'an early and striking case of technological transfer' (Krzyszkowska 2005, 74).

Sources/Suggestions for further reading:

- O. Krzyszkowska. 2005. Aegean Seals: An Introduction. London (Institute of Classical Studies): 72–74.

Maria Anastasiadou

Previous

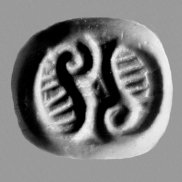

The Parading Lions Group

This is one of the earliest style groups of seals known in the Aegean. Its characteristic traits are: the use of hippopotamus ivory as a manufacturing material; engraving by hand tools; lion iconography on the seal face; employment of two-sided stamp cylinders as a seal form.

The lions which are often shown walking the one behind the other using the contour of the seal face as ground give the group its name. Other motifs typical of these seals are scorpions, leaves and spirals.

These are the first Minoan seals with the depiction of representational motifs, including human figures. They are also the first in which an 'exotic' material, hippopotamus ivory, is regularly used and 'exotic' imagery, the lions, is attested. Hippopotamus ivory would have been imported, possibly from Egypt. Lions, which did not live in Crete in this period, could have been physically seen in expeditions outside Crete or via their depictions in imported artifacts.

These objects represent elaborate and perharps even prestigious artifacts that would have signified access to exotic knowledge via their material and imagery. Their elaboration must reflect rising complexity in the social structures of Prepalatial Crete, which eventually led to the emergence of the Minoan palatial societies some centuries later. It is even possible that the seals of the Parading Lions Group also actively contributed in this complexity by their use, eventually playing an active role in the development of palatial societies in Crete (Anderson 2016).

Sources/suggestions for further reading:

- E. Anderson. 2016. Seals, Craft and Community in Bronze Age Crete. Cambridge and New York (Cambridge University Press).

Maria Anastasiadou