Planet Population is Plentiful

11 January 2012

Embargo Time: Wednesday, 11 January 2012, 7 pm (CET), (1 pm US Eastern Time)

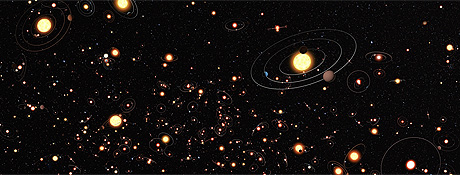

Illustration: European Southern Observatory (ESO) / M. Kornmesser

There is on average at least one planet orbiting every star in the Milky Way. This remarkable conclusion comes from an international team of astronomers, including leading scientists from the Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg (ZAH), who used a method known as gravitational microlensing. After a six-year search that surveyed millions of stars, the researchers conclude from their comprehensive statistical analysis that planets orbiting stars, or “exoplanets”, are the rule rather than the exception. The results will appear in the journal “Nature“ on 12 January 2012.

Over the past 16 years, astronomers have detected more than 700 exoplanets and have started to probe the spectra and atmospheres of several of these remote worlds. One basic question remains: How commonplace are planets in our Milky Way? Most currently known exoplanets were found either by detecting the effect of the gravitational pull of the planet on its host star or by catching the planet as it passes in front of its star and slightly dims it. Both of these techniques, i.e., the radial velocity and transit methods, are most sensitive to planets that are either very massive or close to their stars, or both. Until now many exoplanets were simply overlooked because they were beyond the limits of detection of these techniques.

Prof. Dr. Joachim Wambsganss, Director of the Centre for Astronomy of Heidelberg University, and his collaborators use another method to search for exoplanets. Gravitational microlensing reveals them by measuring the effect of their gravitational fields on the light of background stars. In this method, the star and its planet act like a lens, focussing the light rays of the background star to the observer and hence making this star appear brighter for several days. The change in brightness over time, the light curve, has a very characteristic shape. The planet’s influence is often measurable for only a few hours. This technique makes it possible to detect planets located further away from their stars and over a broader range of masses, and it is well suited for statistical analyses. Yet the probability for detection is extremely low. “In order to detect a single stellar gravitational microlensing event, the brightnesses of several million stars need to be measured several times a week. And even if all the lensing stars have a planet, this planet reveals itself in less than one percent of cases,” explains Prof. Wambsganss.

“We combed through six years of microlensing observations. Remarkably, these data show that planets are more common than stars in our Galaxy”, says the lead author of the Nature paper, Dr. Arnaud Cassan, a former postdoc of Prof. Wambsganss at the ZAH, now with the Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris (France). The results of the study are largely based on work that Dr. Cassan did during his time in Heidelberg. For the investigations, the scientists from Australia, Austria, Chile, Croatia, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, New Zealand, Poland, South Africa and the US – among them researchers from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) – used data from the PLANET (Probing Lensing Anomalies NETwork) and OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) observational teams.

Between 2002 and 2007, the scientists repeatedly measured the brightnesses of several million stars. They observed a total of 3,247 gravitational microlensing events generated by stars. Three of these light curves were clearly planets: one “super-Earth”, one Neptune-like planet and another with a mass similar to Jupiter. The international research team combined the data of these three discoveries with that of seven other exoplanets that had likewise been found through gravitational microlensing. Also included were a large number of stars observed over the six years where no planets were detected. According to Dr. Cassan, the non-detections were just as important for the statistical analysis as the detected planets.

By comparing the data with intensive computer simulations, the astronomers concluded that approximately one in six stars is being orbited by a Jupiter-like planet. The analysis also indicated that roughly half of all stars have planets with the mass of Neptune, and two-thirds host a “super-Earth”. The survey was sensitive to planets between 75 million to 1.5 billion kilometres from their stars and with masses ranging from five times the mass of the Earth up to ten Jupiter masses.

Original publication:

A. Cassan, D. Kubas, J.-P. Beaulieu, M. Dominik, K. Horne, J. Greenhill, J. Wambsganss, J. Menzies, A. Williams, U. G. Jørgensen, A. Udalski, D. P. Bennett, M. D. Albrow, V. Batista, S. Brillant, J. A. R. Caldwell, A. Cole, Ch. Coutures, K. H. Cook, S. Dieters, D. Dominis Prester, J. Donatowicz, P. Fouqué, K. Hill, N. Kains, S. Kane, J.-B. Marquette, R. Martin, K. R. Pollard, K. C. Sahu, C. Vinter, D. Warren, B. Watson, M. Zub, T. Sumi, M. K. Szymanski, M. Kubiak, R. Poleski, I. Soszynski, K. Ulaczyk, G. Pietrzynski & £. Wyrzykowski: One or more bound planets per Milky Way star from microlensing observations. Nature (12 January 2012).

Note to news desks:

Digital pictures are available from the press office.

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Joachim Wambsganss

Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg

(ZAH)

Phone: +49 6221 54-1800

Email: jkw@uni-hd.de

Carolin Liefke

ESO Science Outreach Network

House of Astronomy (Heidelberg)

Phone: +49 6221 528 226

Email: eson-germany@eso.org

Communications and Marketing

Press Office

Phone: +49 6221 542311

presse@rektorat.uni-heidelberg.de