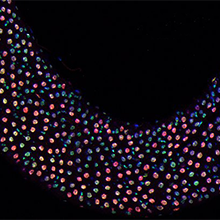

How cells in the colon regenerate

Photo: Garcia del Arco / Ehrhardt

The intestine of many organisms must be able to renew itself to recover from environmental insults like bacterial infections. This renewal is made possible by a small number of intestinal stem cells which divide and produce daughter cells throughout their lives. The daughter cells differentiate into highly specialised gut cell types. Researchers at Heidelberg University have studied these processes in the fruit fly and gained new insights into the role of centromeric proteins that largely regulate cell division. The studies reveal that these proteins also play an important part in cell differentiation and tissue renewal. The results of the research were published in the journal “Cell Reports”.

The researchers at the Centre for Molecular Biology of Heidelberg University (ZMBH) investigated stem cells in Drosophila melanogaster – the fruit fly – midgut, which is functionally and structurally similar to the human intestine. Here, the intestinal stem cells divide asymmetrically: whereas one daughter cell remains undifferentiated and continues to divide, the other cell differentiates and loses its ability to divide. The Heidelberg study was based on the observation that centromeric proteins, which are essential for actively dividing cells, were also detectable in intestinal cells that are no longer dividing.

Dr Ana García del Arco from the research team led by Prof. Dr Sylvia Erhardt discovered that centromeric proteins are also passed on asymmetrically: whereas a protein called CENP-C remains in the stem cells of the intestines and cannot be detected in differentiating cells, the protein CENP-A is found in both the differentiating daughter cells and the undifferentiated stem cells. However, the daughter cells inherit only newly synthesised proteins, whereas the pre-existing proteins remain in the stem cells. Prof. Erhardt’s team was also able to show that CENP-A and its interacting partner CAL1 are essential for the survival of differentiated cells and are required for regeneration signalling to the stem cells.

The study carried out in cooperation with Prof. Dr Bruce Edgar of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City (USA) also uncovered that CENP-A and CAL1 play a role in tissue renewal by regulating highly specialised cell cycles that do not involve cell division. According to Prof. Erhardt, equivalent proteins found in humans are often misexpressed in human tumours. “Future studies need to explore the newly discovered function and asymmetrical inheritance of centromeric proteins to gain a better understanding of these factors in the development of differentiated tissue, stem cell regeneration, and cancer formation,” stresses the researcher.